Tony Whatling - July 1939 to November 2024

Tony Whatling – July 1939 to November 2024

Tony Whatling (July 1939—November 2024)

Tony Whatling’s passing away in Ely Cambridge in November 2024 of a rare neuromuscular disorder has left the mediation profession in the United Kingdom with a void that will be difficult to fill. Born in Glasgow, Scotland, the son of a builder father and a homemaker mother, Tony grew up in Suffolk where he attended a local school and started his life as a printer’s assistant. Soon thereafter he joined the Royal Air Force as a nurse and spent nine years with them with a stint in Fontainebleau, France. On his return to England he was posted to Wiltshire as an evacuation clerk attending to injured returning airmen and allocating them to different hospitals for treatment and rehabilitation. It was then that he acquired a passion for social care.

3 judges if the High Court of Bombay taught in this programme.

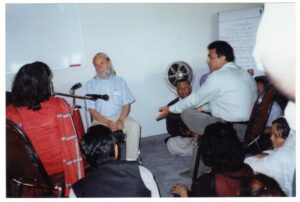

Photo Ray Virani

With his vast experience, Tony engaged with child care, adult mental health, family therapy, psychotherapy and area team management, as he studied for an MSc in the “Sociology of Mental Health” leading to his heading the Social Work Education Department at the Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge — a position he held for 10 years. With over 35 years’ experience as a mediator consultant and trainer, Tony went on to write 3 books distilling his vast experience in each of these fields, with a view to imparting practical skills to students, policy planners and practitioners. These are: Mediation Skills and Strategies — A Practical Guide; Mediation and Dispute Resolution — Contemporary Issues and Developments; and Dealing with Disputes and Conflicts — a Self Help Tool-Kit for Resolving Arguments in Everyday Life.

Accordingly, it is largely in the field of family mediation that Tony’s contribution will be remembered. It must be noted that he was not alone in this process but was part of a small group of people such as Lisa Parkinson, Henry Brown, Marion Roberts, Sonia Shah-Kazemi, Janet Walker and others. With his vast practical experience, Tony’s voice was persuasive. He helped define the contours of the profession by constantly reminding his trainees what mediation was not, regardless of its close resemblance to many other professions in the social care firmament. By so doing, he was able to uphold the fundamental uncompromisable principles of mediation while at the same time embracing new knowledge from a wide range of disciplines in the service of a profession that some 40 years ago was not really known in the UK. One area which he found limiting was the model that was being used in the Anglo-American Common Law world. He found this model to be a highly individualistic, problem-solving, satisfaction-seeking, atomistic one which he felt did not provide the transformative experience that non-adversarial dispute resolution was meant to deliver. Through the training he did Tony constantly interrogated this model and contributed to its adaptation.

My first contact with Tony took place in the summer of 2000 when His Highness the Aga Khan, Imam (spiritual leader) of the global Shia Ismaili Muslim community decided to refurbish the centuries-old practice of non-adversarial dispute resolution (known in Islamic juridical thought as sulh) in the Ismaili community worldwide. Some 14 years earlier the Aga Khan had promulgated a global constitution for his community in which he provided for Conciliation and Arbitration Boards (CABS) which were manned by outstanding volunteers (both men and women) from within the community. The Aga Khan wanted to see the modern principles of mediation and its developing practice suitably integrated into a communitarian culture. Such mediation, he felt, would work best if it embraced the ethical values of Islam such as care and compassion for those in conflict, concern for the marginalised in society and the resolution of conflict through non-adversarial principles. The National Family Mediation, a leading training institution in the UK was assigned the task of training heads of the CAB system then from some 16 jurisdictions worldwide, and Tony was designated as the lead trainer. Given his cultural sensibilities Tony recognised very quickly that the model used for training was inadequate for a community that espoused a relational culture. Here he distinguished his leadership qualities in instantaneously improvising with fellow trainers, Lorraine Bramwell and Marion Roberts a pedagogy that was more germane to the Ismaili community’s ethos. While Chris Oswald a fellow trainer helped implement a small pilot project on training future trainers. With a need for the rollout of the main training programme globally, Tony’s professional services were elicited by the Aga Khan’s Secretariat in France to lead the training programme under my overall coordination.

Tony was ready for the challenge and over a 12-year period the Ismaili CAB training programme trained some 1,400 family and commercial dispute mediators with a small core team of trainers which included Lawrence Kershen (then QC) of the UK and Rupert Watson, Solicitor and Mediator of Kenya, who were both Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution (CEDR) qualified trainers. UK National Conciliation and Arbitration Board’s (NCAB) child psychologist trainer Rukhsana Abdullah and Ray Virani of Atlanta with years of experience working with the CAB system in the USA, became the main interlocutors with the NCABs in each country where training was to be conducted. This included Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh in South Asia, Afghanistan and Tajikistan in Central Asia, Syria in the Middle East, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania in East Africa, Portugal in the EU, and Canada, the UK and the USA. Training programmes were also conducted for personnel from Iran, the UAE, Mozambique and Australia, countries which at that time did not have official CABs in their jurisdiction.

Tony’s presence in these programmes was somewhat incongruous. With his light blue eyes exuding a sense of calmness, he was initially some sort of a mystery. Sporting a blonde ponytail and dressed elegantly at times with his brocaded paisley waistcoats (crimson, gold and grey) and floral ties and at others in a beautifully cut shalwar kameez, he looked like a psychedelic guru but he very quickly won the hearts of all those who came into contact with him purely by his sense of cultural understanding and accessibility. He often started the session by calling for silence in the language of the participants. “Khamosh, Khamosh!” (silence) he would say in Pakistan, while in India when a tea break was over he would call out “jaldi, chalo, chalo” (quickly, let’s start).

The training videos we commissioned with NCAB mediators (where people could not believe these were not professional actors) had to be professionally dubbed in the languages of the different countries where the rollouts were to take place and often we had the whole class in hysteria as they watched Tony speaking in fluent Hindi/Urdu, Arabic, Farsi and Portuguese explaining specific terms such as mutualising, normalising, summarising, positive reframing and future focus in the vernacular. Above all, it was the gradual adaptation of the model to suit the respective cultures coupled with his readiness to listen to local dispute resolvers to see what would work best in their respective contexts, that made the CAB programme so unique and desirable that members of sister communities in many countries participated in the training process. Tony was always open to new approaches being tried out in the Ismaili programme.

On one occasion he organised a one-day workshop in London with All-Issues Family Mediation specialist Margot Moffitt for the NCAB of UK. On another occasion with NCAB Canada we arranged a weekend programme in Montreal for some 50 CAB mediators from across Canada on the Power of Apology- the first of its kind in Canada. Tony also prepared a module jointly with me on mediation for youth in the Ismaili community which was field tested in the first International Adolescent Education Program(IAEP) in Monterrey California in 2001 where conducted role plays with American Ismaili in a summer camp. In October 2005 The World Mediation Forum at its 5th International Conference in Crans-Montana, Switzerland, invited Tony and me to present a joint paper: Reflective Learnings from the Training Programmes of the Ismaili Muslim Conciliation and Arbitration Boards Globally.

Through Tony’s readiness to adapt mediation to different cultures Family Mediation became better known in the countries where the training programmes were held. In Portugal, the Ministry of Justice asked CAB to train its Julgados de Paz (Justices of the Peace) who form an integral part of their Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) system, while in Syria, some seven High Court judges (all non Ismailis) took part in a training programme held in Salamiyah on the edge of the Syrian desert. In Canada, the Foreign Ministry asked for three persons engaged in cases involving International Interspousal Child Abduction under the 1980 Hague Convention to be trained in family mediation. Carolyn, Tony’s wife, a Samaritan, accompanied us on many of these programmes. In Syria, on completing the training programme, Tony suddenly collapsed at the hotel in Hama and had to be urgently hospitalised where seven doctors, including some of the most outstanding neuro-surgeons operated on him and saved his life. One of our translators Sadruddin Fatoum physically carried Tony down 3 flights of stairs at the hotel where the elevator was notoriously famous for getting stuck to ensure that Tony got into the ambulance in time. Tony was incapacitated for a while but was soon back in the saddle to continue the training programme rollouts.

Never to be rattled by force majeure, in one training programme in Portugal Tony readily agreed to change modes of transport when international aviation was severely disrupted globally through a massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia. We hired a Kombi minibus and drove all night from Lisbon to Paris thus enabling all the international trainers to keep their ongoing appointments in London, Paris and Copenhagen. Tony was also able to cope with local exigencies with equal aplomb. In Kabul, dressed in his Afghan outfit and training in an open yard, he suddenly noticed four bearded young men with Kalashnikovs enter and having no choice we invited them to come in and sit right in front. After hearing Tony explain a few mediation techniques that were translated into Pushto one of them asked the organisers whether Tony would come to give them a training session too.

If I may, I would like to relate two personal anecdotes that gave me a deeper insight into Tony the humanist. On one occasion in 2008 I visited him and Carolyn at their home in Prickwillow, Ely to discuss my PhD thesis which was then coming up for defending and I stayed at their lovely home. Tony picked me up at the station in his convertible blue Scimitar and spent some time looking at a few issues I was not clear on. In the afternoon he took me on a ride on the river on his narrow boat called ‘Piglet’ which he loved steering. As we meandered through the river Lark and entered the Great Ouse, I asked him how he had developed such a deep empathy for people in conflict.

Tony steered and I listened with rapt attention. He related to me the pain of a fractured youth characterised by egregious criticism familial, societal and circumstantial. With a feeling of deep sadness in my heart I asked him how he had overcome his odds in life and survived. I realised that he had miraculously managed to turn adversity in childhood into empathy for the marginalised by seeing value in people who could not see it in themselves. Never one to wallow in self-pity he believed that just as he was able pull himself up by the bootstraps, others could do the same and he was going help people with low self-esteem attain their self-fulfilment in life. On another occasion he related to me a scene he had witnessed in a country in South America of a street peanut vendor near a favela feeding his young grandson while attending intermittently to his clients and how the scene had touched him about our human aspirations that we all espouse for our progeny which are so similar. He had a knack for being able to discern human emotions even when they were not expressed in words by reading the underlying sentiment of familial love between the grandfather and the grandchild. Tony’s solicitude extended even to a derelict piece of wood which he would make beautiful and attractive. An adept at making sculptures of pieces of wood from the forest Tony left me with a promise of a wooden lamp that he was going to make for me and which he delivered to me personally a year later.

During the Aga Khan’s Golden Jubilee visit to Lisbon in 2007, Tony had the opportunity to meet with him. The Aga Khan very graciously acknowledged Tony’s valuable contribution to the CAB refurbishment programme globally and thanked him wholeheartedly for his unstinting commitment. Tony was deeply touched to have had the opportunity to meet the Aga Khan who he respected enormously. Tony, a constant learner and cultural navigator, brought his international learning from the Ismaili programme back into his mediation practice in the UK in order to enlarge its ambit and to cater to a more pluralistic demography which the United Kingdom was fast becoming. An ardent listener, a lifelong learner, a compassionate individual and a humanist at heart, Tony was well disposed to be a bridge between different cultures. In characteristic fashion he donated his body for medical research. He is survived by his wife Carolyn to whom he was married for 62 years, sons Steven and Stuart and grandson Tony.

RIP Tony, what you had you gave. What you could you did!

Mohamed M Keshavjee PhD (London)

Former Member Steering Committee of the World Mediation Forum and author of the book Islam Sharia and Alternative Dispute Resolution- Mechanisms for Legal Redress in the Muslim Community, is the 2016 recipient of the Gandhi, King, Ikeda Peace Award for his global work in Mediation and Human Rights Education.

January 2025